#la fuite de Marat

Explore tagged Tumblr posts

Text

'The War of the Districts, or the Flight of Marat…'

Part 1 (of 5)

Some years ago I photographed a fantastic, satirical poem from a compendium of French Revolutionary verse in the BnF (réserve). It’s been gathering virtual dust ever since. But no more! It’s a witty take on a key moment from early in the Revolution, when the Paris authorities pitted themselves against the radical Cordeliers district (under Danton’s leadership). With help from @anotherhumaninthisworld (merci encore!), we managed to produce a rough translation, which I revised, added some footnotes (to clarify the more obscure references) and added this brief intro to put it in context. While the translation is a literal one, I’ve tried to preserve some of the rhyming spirit of the original where possible. So boil the kettle, get a brew on and settle down to an epic account of Maranton vs Neckerette…

In the early hours of 22 January 1790, General Lafayette, commander of the National Guard, authorized a large military force to arrest the radical journalist Jean-Paul Marat, following a request from Sylvain Bailly, the Mayor of Paris, to provide the Chatelet with sufficient armed force [“main-forte’] to enable its bailiff to enforce the warrant.[1] Bailly’s request was in response to the outrage caused by the publication, four days earlier, of Marat’s 78-page Denunciation of the finance minister, Jacques Necker.[2] Marat had moved into the district the Cordeliers district in December to seek its declared protection against arbitrary prosecution.

His best-selling pamphlet denounced Necker – probably the most popular man in France after the King in July 1789 – of covertly supporting the Ancien Régime and working to undermine the Revolution. His accusations included plotting to dissolve the National Assembly and remove the royal family to Metz on 5 October, colluding in grain hoarding and speculation, and generally compromising the King’s honour. The charges were intended to reveal a cumulative (and damning) pattern of behaviour since Necker’s reappointment in July 1788, and again in July 1789. Bearing his Rousseau-derived epigraph, Vitam impendere vero (‘To devote one’s life to the truth’) – now used as a kind of personal branding, Marat adopted the role of “avocat” to ‘try’ Necker before the court of public opinion.[3] Its general tone came in the context of a wider distrust of international capitalism, with which Necker was closely associated, and which appearted to violate many traditional values.[4] For those interested in the nitty gritty, here’s a footnote explaining why Marat had completely lost faith in Necker.[5]

It caused such a sensation that the first print-run sold out in 24 hours. Most of the radical press hailed Marat’s audacity in challenging Necker’s ‘virtuous’ reputation, while providing invaluable publicity for his pamphlet. The legal pursuit of Marat was largely prompted by the rigid adherence of the Chatelet to Ancien Régime values against the offence of libel (attacking a person in print).[6] I suspect that Marat was hoping a high-profile campaign against Necker would help to establish his name in the public eye by provoking a strong response. However, this was one of the rare occasions when Necker delegated his defence to ‘hired’ pens, providing Marat with valuable extra publicity.

If libel was the main reason for going after Marat, the impetus for pursuit was further motivated by wider political concerns over the extreme volatility that had gripped Paris since mid-December. After pre-emptive popular action in July and October against perceived counter-revolutionary plotting, a new wave of similar rumours was seen by many as a signal that the thermometer was about to explode again. The arrest of the marquis de Favras on Christmas Eve, for allegedly conspiring to raise a force to whisk the King away to safety, assassinate revolutionary leaders, and put his master, Monsieur (the King’s middle brother) on the throne as regent, only served to intensify popular fears. This, combined with the continuing failure to prosecute any royal officers, including the baron de Besenval, commander of the King’s troops around Paris during 12-14 July – who would be acquitted on 29 January for ‘counter-revolutionary’ actions – led to large crowds milling daily outside the Palais de Justice, as the legal action against both men dragged on through January.[7] On the 7th January, a bread riot in Versailles led to the declaration of martial law; on the 10th, a large march on the Hotel de Ville had been stopped in its tracks by Lafayette; on the 11th, there was an unruly 10,000-strong demonstration, screaming death-threats against defendants and judges, in the worst disturbances to public order since the October Days march on Versailles (and the most severe for another year); and on the 13th, tensions were further exacerbated by a threatened mutiny amongst disgruntled National Guards, which was efficiently snuffed out by Lafayette.[8] As a result, Marat’s Denunciation, and earlier attacks on Boucher d’Argis, the trial’s presiding judge, were seen as encouraging a dangerous distrust towards the authorities. Hence the pressing need to set an example of him.

So much for the background. Do we know anything about the poem’s authorship? it appeared around the same time (July/August) as Louis de Champcenetz & Antoine Rivarol’s sarcastic Petit dictionnaire des grands hommes de la Révolution, par un citoyen actif, ci-devant Rien(July/Aug 1790), which featured a brief entry on how Marat had eluded the attention of 5000 National Guardsmen and hid in southern France, disguised as a deserter. These figures would become the subject of wildly varying estimates, depending on who was reporting the ‘Affair’ – all, technically, primary sources! The higher the number of soldiers, the greater the degree of ridicule.[9] Contemporary accounts ranged from 400 to 12,000, although the latter exaggerated figure, included the extensive reserves positioned outside the district.[10] Since the poem also suggests around 5000 men, this similarity of numbers, alongside other literary and satirical clues, such as both men’s involvement in the Actes des apôtres, and the Petit dictionnaire’s targeting of Mme de Stael, suggest a possible common authorship.[11] While the poem took delight in mocking the ineptitude of the Paris Commune, the lattertook aim at the pretensions of the new class of revolutionary. While it is impossible to estimate the public reception of this poem, its cheap cover price of 15 sols suggests it was aimed at a wide audience. It was also republished under at least two different titles, sometimes alongside other counter-revolutionary pamphlets.[12]

Both act as important markers of Marat’s growing celebrity, just six months after the storming of the Bastille. A celebrity that reached far beyond the confines of his district (now section) and readership (which peaked at around 3000).[13] Marat was no longer being spoken of as just a malignant slanderer [“calomniateur��] but as the embodiment of a certain revolutionary stereotype. While he lacked the dedicated ‘fan base’ of a true celebrity, such as a Rousseau, a Voltaire or (even) a Necker, he did not lack for public curiosity, which was satisfied in his absence by a mediatized presence in pamphlets, poems, and the new lexicology.[14] For example, Marat would earn nine, separate entries in Pierre-Nicolas Chantreau’s Dictionnaire national et anecdotique (Aug 1790), the first in a series of dictionaries to capitalize on the Revolution’s fluid redefinition of language.

There seems little doubt that Marat’s Denunciation was intended to provoke the authorities into a strong reaction, and create “quelque sensation”, of which this mock-heroic poem forms one small part.[15] It would prove a pivotal moment in his revolutionary career, transforming him from the failed savant of 1789 to a vigorous symbol of press freedom and independence in 1790. Who knows what might have happened, if, as one royalist later remarked, the authorities had simply ignored this scribbling “dwarf”, whose only weapon was his pen.[16]

I'll post the 3 parts of the poem under #la fuite de Marat. enjoy!

[1] The Chatelet represented legal authority within Paris.

[2] Dénonciation faite au tribunal public par M. Marat, l’Ami du Peuple, contre M. Necker, premier ministre des finances (18 Jan 1790).

[3] The slogan was borrowed from Rousseau’s Lettre à d’Alembert, itself a misquote from Juvenal’s Satires (Vitam inpendere vero = ‘To sacrifice one’s life for the truth’).

[4] See Steven Kaplan’s excellent analysis of the mechanisms of famine plots and popular beliefs in the collusion between state and grain merchants. In part, this reflected a lack of transparency and poor PR in the state’s dealings with the public. During 1789-1790, when anxieties over grain supply were the main cause of rumours and popular tension, Necker made little effort to explain government policies. The Famine Plot Persuasion in Eighteenth-Century France (1982).

[5] As a rule, the King, and his ministers, did not consider the workings of government to be anyone’s business, and was not accountable to the public. However, in 1781, Necker undermined this precedent by publishing his Compte-rendu – a transparent snapshot of the royal finances – yet on his return in 1788, he failed to promote equivalent transparency over grain provision. In consequence, local administrators suffered from a lack of reliable information. Given the underlying food insecurity that followed the poor harvest of 1788, any rumours only unsettled the public. The most dramatic example of this came in the summer of 1789, when rumours of large-scale movements of brigands & beggars created the violent, rural panic known as ‘The Great Fear’. It was Necker’s continuing silence on these matters that lost Marat’s trust.

[6] Necker had a history of published interventions defending himself before the tribunal of public opinion, confessing that a thirst for gloire (renown) had motivated his continual courting of PO, then dismissing it as a fickle creature after it turned against him in 1790. eg Sur l’Administration de M. Necker (1791). For the best demonstration of continuity with Ancien Régime values after 1789, see Charles Walton, Policing Public Opinion in the French Revolution (2009).

[7] The erosion of Necker’s popularity began on 30 July after he asked the Commune to grant amnesty to all political prisoners, including Besenval.

[8] While the evidence was slight, Favras’ sentence to be hanged on 18 February made him a convenient scapegoat, allowing Besenval and Monsieur to escape further action. See Barry M. Shapiro, Revolutionary Justice in Paris, 1789-1790 (1993).

[9] The most likely figure appears 300-500. See Eugène Babut, ‘Une journée au district des Cordeliers etc’, in Revue historique (1903), p.287 (fn); Olivier Coquard, Marat (1996), pp.251-55; and Jacques de Cock & Charlotte Goetz, eds., Oeuvres Politiques de Marat (1995), i:130*-197*.

[10] For example, figures cited, included 400 in the Révolutions de Paris (16-23 Jan); 600 (with canon) in Mercure de France (30 Jan), repeated in a letter by Thomas Lindet (22 Jan); 2000 in a fake Ami du peuple (28 March); 3000 in Grande motion etc. (March); 4000 in Révolutions de France; 6000 (with canon) in Montjoie’s Histoire de la conjuration etc. (1796), pp.157-58; 10,000 in Parisian clair-voyant; 12,000 in Marat’s Appel à la Nation (Feb), repeated in AdP (23 July), reduced to 4000 in AdP (9 Feb 1791), but restored to 12,000 inPubliciste de la République française (24 April 1793).

[11] “Five to six large battalions/Followed by two squadrons” = approximately 5000 men (4800 + 300). A royalist journal edited and published by Jean-Gabriel Peltier, who also appears the most likely publisher of this poem.

[12] For example, Crimes envers le Roi, et envers la nation. Ou Confession patriotique (n.d., n.p,) & Le Triumvirat, ou messieurs Necker, Bailly et Lafayette, poème comique en trois chants (n.d., n.p.). Note the unusual use of ‘triumvirate’ at a time when this generally applied to the trio of Antoine Barnave, Alexandre Lameth and Adrien Duport.

[13] By the time the poem appeared, the Cordeliers district had been renamed section Théåtre-français, following the administrative redivision of Paris from 60 districts to 48 sections on 21 May 1790.

[14] For the growth of mediatized celebrity, see Antoine Lilti, Figures publiques (2014).

[15] As Marat explained in a footnote (‘Profession de foi’) at the end of his Denunciation, “Comme ma plume a fait quelque sensation, les ennemis publics qui sont les miens ont répandu dans le monde qu’elle était vendue…”

[16] Felix Galart de Montjoie, Histoire de la conjuration de Louis-Philippe-Joseph d’Orléans (1796), pp.157-58.

#la fuite de Marat#french revolution#poetry#counter-revolutionary#Jean-Paul Marat#Antoine de Rivarol#Louis de Champcenetz#1790#libel#Jacques Necker#General Lafayette#marat

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

La rhétorique c’est pour les foules, aux chefs il faut du répondant, le vrai répondant c’est la Banque. C’est là que se tiennent les clefs de songe, le petit Nord et le grand secret, les souffles de la Révolution. Pas de banquiers pas de remuements de foule, pas d’émotion des couches profondes, pas de déferlements passionnels, pas de Cromwell, pas de Marat non plus, pas de fuite à Varennes, pas de Danton, pas de promiscuité, pas de salades. Pas de Robespierre qui réside à deux journées sans bourse noire. Qui ouvre les crédits mène la danse.

Louis-Ferdinand Céline – Les beaux draps (1941)

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Marat’s response to Robespierre, on the fate of the king

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Quelques réflexions sur “Un peuple et son roi” (spoilers mineurs)

Je viens enfin de voir Un peuple et son roi. Globalement, ce film m’a bien plu : on voit les événements du point de vue du peuple, ce qui est devenu très rare. Cela m’a rappelé La Marseillaise de Renoir, mais avec des techniques contemporaines pour rendre les décors, les costumes, des scènes de nuit, etc. C’était également un beau film — du moins d’après mes propres sensibilités, car je ne prétends à aucune expertise dans ce domaine.

En quittant le cinéma, j’ai entendu dire que ce film faisait “plus documentaire que film” (sous-entendu de fiction). Je ne suis pas tout-à-fait d’accord. Du point de vue historique, je n’ai pas grand-chose à en redire : il y a des choses qui ont été omises ou qui auraient pu être plus développées, mais tout ce qui a été montré était plus ou moins juste. (Les débats d’assemblée étaient tronqués, et c’est normal ; à côté des citations exactes, on a mis des paroles improvisées ; mais on n’a dénaturé le rôle ni le discours de personne parmi les personnages réels.)

Mais c’est aussi un film beaucoup trop fragmentaire pour être qualifié de documentaire : si l’on n’avait pas de bases sur les événements de la Révolution, on serait totalement perdu, j’en suis sûre. Franchement, je ne sais pas si cet aspect me plaît ou pas. Je n’aurais pas préféré que le film se fasse manuel d’école à l’instar de La Révolution française (1989), mais je pense que certains points auraient pu quand même être un peu plus développés. Il me semble que le mieux réussi sous l’optique à la fois de rendre clairs les enjeux et d’impliquer les protagonistes, c’est la crise de Varennes, suivi de près par le 10 août.

Par contre, je trouve très intéressant le choix de commencer le film juste après le 14 juillet et j’ai bien aimé la façon originale dont on s’y est pris : on montre la valeur à la fois symbolique et matérielle de la destruction de la Bastille à travers le fait, auquel on ne pense en général pas, qu’elle a dû permettre enfin aux habitants du faubourg Saint-Antoine qui vivaient à l’ombre de la forteresse de voir le soleil. J’ai trouvé ce moment vraiment beau.

La transition aux journées d’octobre était plus décevante, c’était trop abrupte et je ne crois pas que la compréhension des enjeux ait été bien servie par le début in medias res. Mais il se peut aussi que cette frustration vienne d’un des défauts — somme toute mineur, je suppose — du film. C’était sans doute pour des raisons budgétaires que je peux très bien comprendre, mais il y avait pas mal de scènes où il n’y avait tout simplement pas assez de figurants, et les journées d’octobre étaient l’un des exemples les plus marquants. On a l’impression que les participant-e-s n’étaient pas plus de quelques dizaines. De même pour les membres des Assemblées. Mais, encore une fois, comme il s’agit vraisemblablement de contraintes budgétaires, je ne vais pas tenir rigueur aux réalisateurs.

Je crois que c’était la même personne qui disait que le film “faisait trop documentaire” qui a émis l’opinion que, à cause de la nature fragmentaire du film, les personnages principaux étaient sous-développés. Je ne suis pas du tout d’accord, je les ai trouvés au contraire très attachants. Mais bon, j’ai un faible pour les personnages qui représentent plus que des individus. Mon roman préféré ce n’est pas Les misérables pour rien. ;)

Le film n’est pas sans ses défauts. Je ne sais pas si moi j’aurais choisi de prendre le point de vue du rapport du peuple au roi. C’est vrai que sans choisir un angle d’attaque en particulier, il aurait été difficile de ne pas partir dans tous les sens. C’est vrai aussi que si ce rapport a été présent dans d’autres films, le fait de s’y focaliser est assez original, surtout en privilégiant le point de vue du peuple (même si celui du roi n’est pas entièrement absent). Dans cette optique, je peux comprendre qu’on n’ait pas montré davantage des actions de Louis XVI et à quoi ressemblait concrètement son double jeu, même s’il aurait été bien d’en voir un tout petit peu plus pour mieux comprendre la réaction des autres personnages. Encore une fois, c’est très bien fait pour la fuite du roi, mais pas toujours pour le reste.

Quant à Louis XVI lui-même, j’ai été moyennement convaincue. Je pense que son rêve, où il voit trois de ces prédécesseurs qui lui reprochent d’avoir quitté Versailles ne marche qu’à demie, au mieux. Qu’est-ce que ça pouvait bien faire — même dans l’imagination de Louis XVI — à Henri IV et à Louis XI que leur lointain successeur quittait Versailles ? D’ailleurs, pourquoi aurait-il rêvé de trahir l'héritage de Louis XI, qui était généralement regardé comme un mauvais roi même par les royalistes ? Sûrement Louis XII aurait été un meilleur choix ? D’ailleurs, si le sentiment de ne pas être à la hauteur et de trahir ses ancêtres était sans doute présent chez Louis, on ne montre pas assez le lien entre sa religiosité et ses convictions absolutistes. Mais enfin, c’est encore une critique relativement mineure, puisque ce n’est pas son point de vue qui est privilégié, et fort heureusement.

J’ai vu quelque part un compte rendu qui disait que le film se fait parfois le reflet de notre sensibilité actuelle sans prendre en compte les préoccupations de l’époque. L’auteur évoquait en particulier le fait que la dernière opinion mise en avant pendant le procès du ci-devant roi (mais pas la dernière énoncée, puisqu’on a laissé la parole au véritable dernier opinant pour clore le vote) était celle de Condorcet. Ce n’est sans doute pas une coïncidence, on est d’accord, mais on a laissé la parole beaucoup plus longuement à Saint-Just et à Robespierre et on a pris un échantillon des votes de tous bords, du coup je ne vois pas vraiment à en redire sur ce point. On pourrait également citer le fait que les femmes s’intéressent surtout au suffrage et moins au droit d’être armées, mais ce n’est pas comme si de telles réclamations étaient totalement anachroniques et comme il s’agit en tout cas d’un personnage fictif, je ne vais pas m’en plaindre non plus.

Il faut dire que purement côté ressemblance (car le jeu de tous les acteurs était excellent, pour autant que j’en puisse juger), la distribution aurait pu être mieux, surtout en ce qui concerne Robespierre et Louis XVI — et Danton aussi, dans un moindre mesure — qui n’étaient pas du tout ressemblants. Ce qui était assez énervant, vu que ce sont les personnages historiques qu’on voyait le plus souvent. D’un autre côté, le Marat et le Camille Desmoulins n’étaient pas mal. Danton était un peu trop joli, mais il avait au moins l’embonpoint qui manquait à Louis XVI. Et puis Saint-Just était sans aucun doute le meilleur que j’ai vu à l’écran, du coup l’échec n’a pas été total de ce côté.

Enfin, côté défauts, il n’y avait pas de personnages — ni même, je crois, des figurants — de couleur alors qu’il y en avait très certainement à Paris à cette époque, y compris à la prise de la Bastille et à celle des Tuileries. Je comprends qu’on n’ait pas voulu montrer les débats autour des colonies, puisque ce n’est pas le thématique qu’on a adopté, mais ils auraient au moins dû penser à rendre visible la présence des hommes et des femmes de couleur. C’est vraiment dommage, surtout dans un film où il s’agit de mettre en lumière des acteurs de l’histoire qui ont tendance à être marginalisés, surtout dans les récits fictifs...

Mais en tout, je recommande vivement ce film. Rien que le point de vue adopté et le souci de ne pas dénaturer les événements historiques ni les différentes perspectives lui fait mériter de l’attention, et en plus j’ai trouvé certains moments vraiment émouvants. C’est un beau film sur la Révolution comme il n’y en a pas des masses.

19 notes

·

View notes

Photo

UN PEUPLE ET SON ROI - Quel scénario ultime et fantastique que celui de la Révolution Française! Impossible d’imaginer plus épique, plus puissant, plus intense et passionnant que ce que vécurent les français de toutes les catégories sociales à l’heure du “sacrifice” de la Monarchie…. La Grande Histoire dépasse souvent les fictions les plus rocambolesques, celle de la révolution Française reste ma préférée, pour toujours!

Après le très bon Exercice de l´État, Pierre Schoeller tente cette fois un exercice plus compliqué et plus risqué, celui du réalisateur qui raconterait les rapports entre le peuple et son Roi à l’heure de la révolution. Déification, adoration, détestation, “hainamouration” disait Lacan; le peuple français ne finira jamais de se languir de celui dont il a demandé l’exécution publique. L’instauration de la démocratie était-elle contradictoire avec cet amour impossible que les français vouaient à Louis XVI ? L’égalité des citoyens admet-elle l’idée d’un pouvoir incarné par “un seul homme”? L’angle d’attaque pour rendre compte des enjeux (jusqu’à ce jour indélébiles) de la révolution qui fit trembler toute l’Europe, était le bon, même s’il n’est pas traité frontalement ou très mal.

Les discussions qui rendent compte du double-bind français sont récitées, surfaites, clammées… Trop de (grands) acteurs éclipsent l’idée de peuple, alors que le Roi semble complètement effacé et résigné devant le rôle qu’on lui demande de jouer. Il manque toute l’exaltation, le questionnement, la douleur, les incompréhension que l’ensemble des français eurent à traverser. Les voilà réduits à une poignée de parisiens, et confinés dans des anecdotes trop peu significatives pour donner de l’intensité à un propos qui s’éparpille à peine amorcé dans la moindre direction. On passe ainsi de tableaux en tableaux juste datés, sans que la relation de causalité entre eux ne soit explicite, au risque de nous embrouiller plutôt que de nous éclairer.

Le film assez académique dans sa forme n’en devient donc pas didactique dans le fond. Car si certaines séquences évoquent l’esprit des docu-fictions, nous sommes ici évidemment privés des explications des historiens. Cette longue fresque, même si elle inclue quelques très belles scènes mémorables, en devient assez décousue et peu lisible.

Mais la confusion prend le relais du réalisme qui manque cruellement à ce scénario. On ne comprend pas grand chose mais on retient de toutes les questions qui surgissent de ce méli-mélo que tout cela restait embrouillé et illisible pour la plupart. Le peuple de Paris n’a jamais fait bloc; à l’image des débats révolutionnaires, il était divisé, perdu, sans repère et surtout plus préoccupé par la faim que par de belles phrases théoriques sur la Liberté et l’Egalité.

Il faut pourtant souligner que toutes les scènes d’Assemblée sont remarquables, elles sont d’une fidélité presque totale aux discours détenus par les Archives Nationales. Le fameux Robespierre reste décevant, il semble bien plus apathique que dans notre imaginaire où il trône en incorruptible effrayant. Quand à Marat, teigneux, extrémiste et hargneux, il évoque un certain personnage odieux du paysage politique actuel que je répugne même à nommer.

La fuite en avant vers la violence, et en définitive vers la Terreur, est assez bien pressentie par la progression du récit. On l’envisage bien mieux pendant les scènes du vote ultime qu’au spectacle d’un peuple de Paris qui finit par paraître inexplicablement assoiffé de sang royal. Quelque chose des conséquences immédiates de cette exécution aurait donné à ce film tout son sens et une portée bien différente. C’est bien parce que le rapport entre le peuple et son Roi était si complexe et tellement ambivalent que la révolution du système exécutif et législatif eut tellement de mal à être effective dans le cœur des hommes. Le film s’achève et on reste sur notre faim quand à ces images manquantes.

NOTE 12/20 - Malgré tous ses défauts, ce (mauvais) film reste un témoignage mérité d’une période trouble et déchirante pour tellement de français. Cette reconstitution en aucun moment réaliste reste quand même une esquisse remarquable de l’écart qui existe entre les bouleversements effectifs visibles des siècles plus tard, et les difficultés de fond qui président à leur aboutissement.

Même si beaucoup de scènes inutiles prennent la place de séquences qui manquent cruellement au récit comme à la compréhension des événements majeurs de cette période, le film reste beau, et éminemment émouvant. Je n’en finis jamais d’être bouleversée de cette époque et aucune représentation ne me lasse à ce sujet.

Sans Twitter ni FaceBook les hommes et les femmes du 18ième siècle savaient se rassembler, se motiver pour des causes communes jusqu’à y perdre leurs vies. Le sens du risque et de l’engagement semble inversement proportionnel à l’étendue des moyens dont on dispose pour défendre des causes vitales.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

UCHRONIQUEMENT FAUX

Cette semaine sortait sur Netflix un animé inspiré de la mythologie, dont la plateforme faisait la promotion de la manière suivante: “Dans la mythologie grecque, il y a des histoires qui n’ont pas été racontées”. Un principe qui m’évoque aussi fortement la manière dont son autre série “La Révolution”, sortie une semaine avant, s’est visiblement construite et qui malheureusement ne se suffit pas à lui-même...

Plutôt très grand fan de cette période historique, j’attendais avec impatience une série qui se montrait assez ambitieuse dans sa volonté de raconter sa propre vision d’un évènement fondateur de notre “récit national” mais qui, à ma grande déception, se retrouve au final bancale et terriblement peu originale.

On peut évacuer d’emblée le reproche de l’inexactitude historique et s’accorder sur le fait qu’il s’agit d’une uchronie comme le clame les défenseurs de la série, et ce à juste titre, sans toutefois omettre que c’est autant un argument qu’un contre-argument, donnant alors la sensation que la série se retrouve prise à son propre jeu. (Spoiler, retenez bien ce paragraphe que l’on nommera la tête du serpent).

Comme l’introduit si bien le show avec une citation de Napoléon, l’Histoire à pour particularité d’être écrite, réécrite, racontée et enseignée par une multitude de profils différents et ce sur plusieurs siècles débouchant inévitablement sur quelques petites “modifications”. D’autant plus lorsqu’il s’agit d’un récit qui a pour but de rassembler une population autour d’idéaux communs : le fameux récit national.

youtube

Prenons pour exemple Jeanne D’Arc, tout le monde connait l’histoire de la Pucelle, conseillée par les archanges, capable de reconnaître le Roi de France, caché au milieu d’une foule sans l’avoir jamais vu, le tout pour aller bouter de l’anglais. En réalité, on omet souvent de raconter que son parcours est plus ou moins une opération marketing “storytéllée” dans l’ombre par Yolande d’Aragon, belle mère du roi désireuse de bousculer une situation bien mal embarquée pour les français. Il en va de même pour la Révolution Française qui ne s’est pas exactement déroulée comme on nous la résume dans les livres d’Histoire. Il existe en réalité toujours un flou sur la célébration du 14 juillet: Prise de la Bastille ou Fête de la Fédération ? Ou plus surprenant encore, cette fameuse prise de la Bastille n’avait en réalité pour but que de “fournir en arme la nouvelle police de Paris devant lutter face aux casseurs de l’époque” (sommairement). D’ailleurs, le 14 juillet n’est qu’un évènement au sein d’un processus long et complexe prenant place sur plusieurs années. Une période aussi importante possède donc une multitude de zones d’ombre dans lesquelles immiscer les mystères les plus profonds ou les théories du complots les plus fumeuses tout en se liant à la vérité historique pour mieux créer le doute du “Et si c’était vrai ?”. Ce que fait très bien la série de jeux vidéo Assassin’s Creed qui nous fait voyager aux travers des grands évènements de l’histoire ou même Dan Brown pour ne citer que deux blockbusters de la pop-culture.

L’uchronie devient donc une formidable arme scénaristique, qui se retourne violemment contre vous lorsqu’elle n’est pas maîtrisée, ce qui est le cas ici. Une arme qui s’amorce avec une seule & simple question: Pourquoi des zombies ? Alors oui j’exagère un peu, techniquement il semble s’agir plus de “zombies-vampires-cannibales” mais bon... Là où il faudrait être subtil, la série tire des traits gros comme des pipelines de gaz et tout devient caricatural au possible, à tel point que l’on comprend tout trop vite tant le show est formaté.

Le point de départ global prend son origine dans le “mythe du Sang Bleu”. Pour faire simple, à cette époque la noblesse cherchait à tout prix à se démarquer des plus pauvres sur tous les points fuyant ainsi paradoxalement “le bronzage”, signe distinctif des paysans qui passaient leurs journées dans les champs. Il fallait donc être le plus pâle possible, la peau en devenant si transparente et si fine que les veines en devenaient visible, donnant l’impression visuelle que le sang était de couleur bleu. Et à partir de là, mettez votre ceinture, tout s’enchaîne en trois points gagnants. 1- Le sang bleu est en fait une malédiction ramenée volontairement par Louis XVI en capturant une sorte de sorcière Vaudou. 2- Les nobles veulent s’en servir pour devenir immortels, doués de supers-sens et insensibles à la douleurs mais ça les rend aussi cannibales (pourquoi ?). Ils vont donc évidemment manger les pauvres (pourquoi pas justes des animaux ?) 3- Un groupe de paysan qui se dénomment “La Fraternité” (vous l’avez) va s’opposer à ce sang bleu pour ne pas être dévoré, croisant comme de par hasard le docteur Guillotin. On peut même supposer que le seul moyen de tuer les immortels sera de leur couper la tête (comme dans Highlander) d’où l’invention de la Guillotine... Ca force légèrement le trait non ? Au final, le contexte de la révolution n’est absolument pas justifié, un tel scénario pouvant amplement prendre place dans un village de Roumanie où les habitants lutteraient contre Dracula himself. Les scénaristes ont même dû s’en rendre compte tant ils vont forcer les monologues des personnages évoquant la lutte des classes pour tenter de rattacher les wagons. Le problème, c’est que ça risque d’aller de mal en pis. Pour cette première saison, en restant objectif on peut presque accepter ces non-subtilité de mise en scène, d’autant plus que l’action se déroule en 1988. Malheureusement, plus l’on va avancer dans les saisons plus ils va être compliquer de placer du vampire dans les Etats-Généraux, Le serment du Jeu de Paume, La marche vers Versailles, La fuite vers Varenne... Quid de Danton, Mirabeau, Robespierre, Desmoulins, Marat ? Sans parler de la Terreur & la Grande Terreur...

Plus l’on va évoluer dans la complexité de la Révolution, plus il va falloir y inscrire et justifier le point de départ de la série, risquant le fait de devoir créer des allusions toujours plus forcées pour tenter de tout faire rentrer dans une case extrêmement manichéenne & très simpliste... Et dans la réécriture historique, plus c’est gros moins ça passe. Pour la suite, deux choix s’offrent à nous: - Soit on s’éloigne du contexte historique, ses petits détails, les grands noms et on poursuit l’aventure en fonçant sur un T-Max en Y pour lutter contre les vampires aux côtés de la fraternité. - Soit on tente d’y coller au plus possible à coup de name dropping pour essayer de caser tout le monde au sein de la théorie du complot la plus fumeuse de tous les temps.

Au final la Révolution n’a que bien peu d’importance, dans le premier cas on s’en moque, dans le second on nous prend pour des idiots tant l’écriture est bâclée. Etrange quand on commence son show en indiquant vouloir en raconter la “vérité”. Pourquoi s’entacher de la Révolution si ce n’est pas pour profiter de ses multiples zones d’ombres ? Oui c’est une uchronie mais est ce que cela doit justifier le bas niveau d’écriture ? Apporter cet unique argument équivaut à se manger la queue, vous invitant donc à vous reprendre votre lecture au paragraphe de la tête de serpent pour, à l’image de la série, tourner en rond.

1 note

·

View note

Text

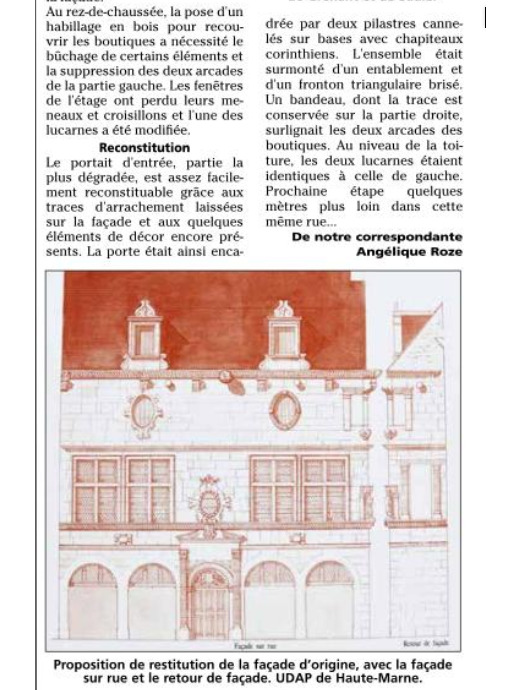

Haute-Marne : Langres à l'heure de la Renaissance III

jhm.fr

https://augustinmassin.blogspot.com/2018/06/haute-marne-langres-lheure-de-la_10.html

Et pendant ce temps là dans la future Haute-Marne, quel était la situation politique et sur le terrain? (...) C'est en qualité de Lieutenant Général du Royaume que François de Guise parvient aux plus hautes fonctions en 1560. L’accession de la famille au gouvernement attise les rivalités des clans, dont le premier épisode aboutit à la répression sanglante d'un complot de mécontents calvinistes, à Amboise, en mars 1560. La mort précoce du roi met les Guise à l'écart mais n'abat pas leur puissance. Pendant la minorité de Charles IX, la régente Catherine de Médicis tente d'ouvrir le dialogue entre les deux parties. Mais l'échec des entretiens entre catholiques et protestants ne fait qu'augmenter les tensions. Même l'édit de janvier 1562, autorisant avec des clauses restrictives l'application du culte réformé hors des villes, ne satisfait personne. C'est dans ce contexte d'excitation extrême que se produit l'irréparable. Le massacre de Wassy, détonateur des guerres de religion Dimanche 1er mars 1562, 1200 protestants assistent au prêche dans la grange qui sert de temple à l' Eglise Réformée de Wassy, installée depuis quelques mois par celle de Troyes. À son retour de Saverne, le duc de Guise et son frère Charles cardinal de Lorraine, accompagnés d'une escorte de gentilshommes armés, pénètrent dans la ville. Surprenant les protestants sur leur lieu de culte, ils perturbent de coups de feu la cérémonie. Y a t-il eu préméditation à la provocation? Toujours est-il qu'ils investissent la grange, tirent sur l'assistance et tous ceux qui tentent de s'échapper, laissant 74 victimes et une centaine de blessés. Le pasteur de Wassy, Léonard Morel, est enfermé dans un cachot de Saint-Dizier. Il y demeurera 14 mois. Les Réformés de la ville se réfugient à Trémilly que détient un seigneur huguenot. Après l'affreux carnage, le duc gagne Eclaron et se dirige lentement vers Paris où la nouvelle du massacre l'a précédé. Il y reçoit un accueil chaleureux qui inquiète les protestants conduits par le prince de Condé. Ceux-ci prennent les armes. La reine mère, Catherine de Médicis devient la proie des factions, la guerre civile a commencé. Première guerre : les réactions protestantes Le cycle des représailles plonge le pays dans l'anarchie. De part et d'autre, les excès font rage dans les campagnes et dans les bourgs. Ils sont orchestrés par les principaux chefs en présence : le duc de Guise, Montmorency... pour les catholiques, le prince de Condé, Coligny...pour les protestants. [...] Le duc de Guise lui-même est assassiné par un huguenot, Poltrot de Méré, à Orléans en février 1563. [...] Condé, chef des protestants, est abattu à son tour en 1569. Coligny, apparaît alors comme son successeur à la tête des huguenots. Introduit à la cour à des fins politiques (règlement du mariage entre Henri de Navarre et Marguerite de Valois), ce dernier prend un tel ascendant sur le roi qu'il devient la cible des Guise et de Catherine de Médicis. ... D'un commun accord, ils décident d'agir pour se débarrasser de Coligny et de ses partisans. Persuadé par sa mère qu'un complot protestant se trame contre sa personne, le roi consent à faire massacrer les huguenots à Paris. Le jour de la Saint-Barthélemy (24 août 1572), les principaux chefs calvinistes sont éliminés. Mais on assouvit aussi des vengeances personnelles : le protestant Antoine de Clermont d'Amboise, héritier du marquisat de Reynel y est assassiné par son cousin et rival de Bussy. Notre région réagit à ces évènements. À Joinville, quatre mois après, Henri de Guise invite la noblesse locale à se rassembler autour du roi. Dans le Bassigny, les protestants répondent violemment aux atrocités parisiennes. Ils incendient Andelot et prennent par surprise le château de Choiseul en avril 1573. À l'initiative du cardinal de Lorraine, ils en sont délogés par les armes : on dénombre 80 exécutions sommaires. Les moines de Morimond on dû se réfugier à Langres pour éviter des représailles, le pays est ruiné. Charles IX meurt en 1574. Son frère, qui lui succède sous le nom de Henri III, est reçu triomphalement à Chaumont en janvier 1575; mais les guerres civiles n'ont pas cessé. L'année suivante, à la demande de Henri de Condé, les 16 000 reîtres du prince palatin, alliés des calvinistes français, reviennent à la charge. Ils franchissent la Meuse, envahissent la France, mettent le Montsaugeonnais à feu et à sang, incendient à nouveau Marcilly, dévastent Le Pailly et le château de style renaissance du maréchal de Tavannes impliqué dans les massacres de la Saint-Barthélemy. C'est en arrêtant les reîtres à Dormans en Champagne que le duc de Guise reçoit sa fameuse balafre. Les villes demeurent en éveil permanent derrière leurs remparts. Langres, Chaumont, Saint-Dizier consacrent des sommes énormes à leur sécurité. Grenant Ce village est bâti sur le Salon (ou Saulon), affluent de la Saône. Plusieurs étymologies sont possibles : selon Dauzat et Rostaing, ce nom exprime probablement un "lieu ou les céréales grènent bien". Selon E. Leclerc et J. Abraham, l'origine de ce nom vient de la langue gauloise (Gravonantos) et signifie "vallée sablonneuse". c'était à Grenant que la voie romaine Langres-Besancon franchissait le Salon. Le pont de pierre actuel, composé de dix arches, construit en 1741 a été restauré en 1820. -L'église reconstruite en 1786 et en partie au 19ème siècle, est dédié à Saint-Martin, évêque de Tours, qui serait passé à Grenant. Il est à noter que, la veille de la fête de ce saint patron, les jeunes conscrits, paraît-il, vont accrocher des images de l'évêque de Tours aux portes des maisons. De 1790 à 1802, Grenant est choisi pour devenir chef-lieu de canton. -Natif du village, Nicolas Colin (Grenant, 12 décembre 1730- Paris, 1er ou 3 septembre 1792) refusa de prêter serment à la constitution civile du clergé. Il fut incarcéré à la prison parisienne de Saint-Firmin avec ces 1 600 prêtres et royalistes massacrés par des sections révolutionnaires, sous l’impulsion de Marat, durant les premiers jours de septembre 1792. -Le village de Grenant est dominé, au Sud, par un relief de 318 mètres d'altitude, le Mont-Rochotte sur lequel a été bâtie la chapelle Saint-Germain. Le saint serait passé par là, lui aussi, et aurait laissé l'empreinte de son pas dans le rocher. Derrière cet édifice, on avait coutume d'enterrer, jusqu'en 1840, les enfants morts sans avoir reçu le sacrement du baptême. Saulles -Ce petit village tire probablement son nom du cours d'eau (le Saulon) en bordure duquel il est situé. -Eglise Saint-Symphorien : 18° (1780) et 19° siècles. (Vierge de la Miséricorde, 18° siècle). -Vieille bâtisse avec échauguette d'angle en bordure de la route. -Château construit en 1761 par Henri Plubel, chanoine de Langres, et restauré en 1842. -En septembre 1944, la vallée du Saulon est empruntée par les colonnes allemandes qui remontent vers le Nord-Est. Le général Brodowski, responsable du massacre d' Oradour le 10 juin, commande l'une de ces divisions en fuite. Le 11 au soir, trois jeunes infirmières et deux FFI sont surpris. Ces deux derniers sont abattus et les jeunes filles atrocement torturées et assassinées (Plaque commémorative). Extraits tirés de "Harmonies haut-marnaises", p.181, p.183 et p.217. Roger Petitpierre, Claude Petitpierre, Guy Salassa, l'Escarboucle Chaumont, 1987, Lire

0 notes

Text

Coda to The War of the Districts, or the Flight of Marat, Heroi-comical poem in three cantos (Paris: n.p., July? 1790)

Part 5 (of 5)

A few words on the aftermath of Lafayette’s failed military expedition, as ‘celebrated’ in this poem. The attempt to arrest Marat completely backfire by helping to transform Marat into a renegade ‘celebrity’, and by boosting sales of his Denunciation. Marat’s escape – recounted with numerous variations – disguised as a soldier, as a woman, even taking off in a balloon! – marked a turning point in his revolutionary career. It also helped to crystallize the reputation of the lawyer Georges Danton, de facto leader of the Cordeliers district, who would be prosecuted (unsuccessfully) in March for threatening to resist Lafayette’s men if they tried to encroach on his territory without the correct legal authorization.[1] After a couple of weeks in hiding, he finally left for exile in London, where he stayed for four months from February to May. His final gesture before leaving was to refund all his paper’s subscriptions.[2]

Marat’s celebrity was further fuelled by the slew of Necker-sponsored anti-Marat (and pro-Necker) pamphlets that appeared over the next few months and the production of at least a dozen separate, counterfeit versions of his Ami du peuple. It was not just Necker loyalists who reacted strongly to this affair. Royalist writers also picked up on the disproportionate reaction, and its humiliating failure, with a mixture of admiration and mocking disdain. Perhaps the most sarcastic response came in the form of this mock-epic poem, which greeted Marat about a month after his return from a four-month exile in England.[3]

Regarding the identity of the “young lady” who helped him escape, there appear to be several candidates. Since these events predate Marat’s known liaison with Simonne Evrard (after June 1790), who would first shelter then ‘marry’ him, this may be a salacious reference to his young assistant, Victoire Nayait. At the time, Nayait was managing his journal’s business affairs, acting as liaison with his publisher, printer and subscribers, when he was in hiding. After Marat’s return from London in May 1790, she disappears without trace.

Another possibility is that he escaped with the help of Comédie-française actress Mademoiselle Fleury [Marie-Anne-Florence Bernady-Nones], whose assistance is also cited in Marat’s earliest biographies by Alfred Bougeart and François Chèvremont. There must be a grain of truth in this, for on 14 February 1794, the former comte de Ferrières, agent for the Committee of General Security, was accused of having released, without authorisation, certain prisoners, including the actresses, Mlle Fleury and Mlle Méscray [Joséphine Mezeray]. In his defence, he cited the fact that Fleury “had once saved Marat”. [4] Further investigation reveals that Mlle Fleury, who had been the mistress of Charles-Armand Tuffin, marquis de La Rouerie, in 1788, married a Doctor Valentin Chevetel, member of the future Cordeliers Club, who lived in the same building as Marat. Chevetel was also a friend of Tuffin, having cared for his sick wife. He would later betray Tuffin’s counter-revolutionary plot, known as ‘La Conjuration Brétonne’, to Danton in October 1792.[5] This reference to Marat’s ‘mistress’enjoyed a suitably salacious, and venal, afterlife, when it was ‘reported’ in a royalist journal, Fouet National (23 Feb) that his silence had been bought by Necker, Bailly and Lafayette for 10,000 livres, and he was now ensconced in the town of M***, in Picardy, with “his little maid” (“petite bonne”).[6] In April 1793, Marat would indeed claim that Necker had tried to buy his silence for a million livres in gold.[7]

After Marat’s great escape, the Révolutions de Paris highlighted Marat’s new status as a revolutionary scapegoat, characterizing these events as a calculated attempt to intimidate all patriot writers, “Souvenez-vous que, parmi les écrivains patriotes, celui sur la tête duquel il fallait frapper pour les effrayer tous, était le sieur Marat, parce que son courage allait jusqu’à la rage, et que sa conviction se changeait quelquefois en délire” (30 Jan). The following issue carried a letter from a National Guardsman, accusing it of being in the pay of mysterious forces, and warning it that they would all repent if they carried on.[8] “Je crois que vous voulez faire le petit Marat. Croyez-moi, ne continuez pas; Marat n’écrit plus; vous pourriez faire de même” (6 Feb). During the Revolution, few figures earned their own eponym, even fewer so early on.[9] Marat’s absence was also noted by readers outside the metropole, with a curé from the Ardèche asking the Révolutions de France, “Vous ne dites plus rien de l’ami du peuple: n’est-il pas encore remonté dans sa guérite [guardhouse/sentry box]? Tout le monde demande ici de ses nouvelles; je vous en demande à vous, au nom de 300 mille Vivarais” (March).

Six months later, Marat would produce his own version of events. He had witnessed the whole affair from the window of a neighbouring house. He put on a round hat and went out with a friend to see what was happening, while awaiting delivery of the next day’s proofs (for his paper). In the middle of the night, he heard a cavalry squadron stop beneath his window but they did not enter. Spotting some spies (“mouchards”) outside the house the next morning, he donned a disguise and left arm-in-arm (“marchant à pas comptés”) with a young lady. He then met some friends in the Jardin de Luxembourg who had arranged another hiding place, but after finding no one there, he returned to an old one, chez Boucher de Saint-Sauveur, stopping his carriage at the Hotel de Ville to see what was happening there (AdP, 23 July).[10] His narrative was intended to demonstrate that he could blow a raspberry at the authorities while risking his personal safety for the patrie.[11]

[1] Danton told the expedition commander that his warrant was invalid without the countersignatures of five Cordeliers commissioners, which they would only provide once it was correctly made out. He threatened to summon a further 20,000 men from the neighbouring faubourg St-Marcel if the National Guard attempted to enforce it without the new warrant.

[2] Jean Massin, Marat (1960), pp.116-117. From London, Marat would publish two further pamphlets: a letter on the legal aspects of his case including a proposal for an independent tribunal (April) and a sequel to his Denunciation (April).

[3] Marat was back in Paris by mid-May. Many of these pamphlets were sponsored by Necker who also had at least one journal (Journal de Paris), and a team of writers working for him, including Jean-Baptiste-Antoine Suard, Dominique-Joseph Garat and Pierre-Louis de Lacretelle.

[4] They were imprisoned in September 1793, along with eleven other members of the Comédie-française, and the novel’s adapter, Francois de Neufchateau, for a ‘suspect’ production of Samuel Richardson’s Pamela. See Alphonse Aulard, Receuil de documents pour l’histoire du club des Jacobins de Paris: Jan 1793 à Mars 1794 (1895), v:652.

[5] See Ghislaine Juramie, La Rouërie, la Bretagne en Révolution (1991), p.8; and Elizabeth Kite, ‘Charles-Armand Tuffin, marquis de la Rouerie etc.’, in Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, vol.59, no.1 (1948).

[6] Cited in Jacques de Cock, Marat avant 1789 (online), p.1649 & Jean Massin, Marat (1966), p.117. The Fouet started as a patriot paper before completely changing editorial direction in February 1790.

[7] Le Publiciste de la République française #177 (24 April 1793).

[8] A reference to its criticisms of Lafayette.

[9] Napoleon, Lafayette, Robespierre, Danton, Brissot, Roland, Hébert and Babeuf were the others.

[10] It appeared just after Malouet’s denunciation in the National Assembly of Marat and Desmoulins for the crime of lèse-nation in their journalism. In the same account, Marat boasted of provoking the authorities with awkward questions and contrasting this against Desmoulins’ cowardly proposal to renounce his offending “écrits”.

[11] As well as providing Marat with a safe house, Boucher de Saint-Sauveur also lent him 1000 livres.

#la fuite de Marat#French Revolution#Jean-Paul Marat#Camille Desmoulins#Mademoiselle Fleury#libel#counter-revolutionary#poetry#Boucher de Saint-Sauveur#Victoire Nayait#comte de Ferrieres#marquis de la Rouerie#sorry for the lonnnng post#perhaps this might kickstart a revival of interest into French Revolution humour?#most of the best stuff comes from the 'other side'#which may be why the record is so quiet on this neglected treasure trove#marat

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anon [Louis de Champcenetz?], The War of the Districts, or the Flight of Marat, Heroi-comical poem in three cantos (Paris: n.p., July? 1790)

Part 4 (of 5)

Last Canto:

“When the sun that lights our way,

Near SAINT-MANDÉ

Had flooded all of PARIS,

With its quicksilver light:

Five to six large battalions

Followed by two squadrons,

Silently advanced

Into OBSERVANCE.

BAILLY knowing the moment

When the troops would be assembling,

Is chatting with his wife,

Who fancies herself a fine lady,

While pouring out the tea,

With a fair degree of glee.

‘MARAT’, she says, ‘will be captured,

How my heart is enraptured!

He sought out of his own vanity

To tarnish your immortality;

But the die is cast.’

‘Oh! my loyal spouse!’

He says to her so tenderly

Promptly back to Mr Mayor;

‘Your speech is quite delightful,

I want to have a child with you.

I find you quite an eyeful,

How I long for you anew.'

‘Moderate your friendship’,

His chaste half says to he;

‘I'm not some flirting girouette,

Just wait until la FAYETTE

Has the rascal under lock and key;’

BAILLY says, ‘I want it desperately.’

NECKER who shines with virtue,

Between his daughter & his wife,

Tasted at that moment

The best day of his life.

‘We will let the joker rot

In the corner of some cell.

He attacks my writings,

He covers me with spleen;

Me! whose noble role

Shines so brightlyeverywhere:

Me! Minister Supreme,

Getting vexed by MARAT.’

STAËL (1) the proud ambassadress,

Felt a noble wrath,

Which made her jaundice blush,

‘My father, console yourself;

I wish to make a satire [1]

Against all the insolent wretches

Which your great talents censor

And dare to slander you.

My dear NARBONNE LARA (2)

Shall help me with this work.

GUIBERT (3) could have done it,

His pen is quite light,

But he no longer knows how to please me;

And in my daring pamphlets

I shall crush CHAMPCENETZ (4),[2]

This caustic character

Whose teasing I detest.’

Her mother, reacting to her zeal,

Addresses both, ‘My children,

For that is what you are;

And when I look at you;

My heart is like my eyes;

I confuse you with each other.

Reflect well upon our glory;

And use the écritoire; [3]

Because it is by this weapon,

That this great Minister is here.

The patriotic horde

Of the MERCIERS & GUDINS, (5)

Avenge us every morning,

From the famished horde

Who crawl under DESMOULINS (a):

Their pension is not enough;

But to defeat the MARATS,

We have the proud escort

Of the SUARDS & GARATS (6).

And if we need more ducats

For this miserly cohort;

Pay them, it’s no big deal,

Since we are not short.

But let’s consider something else,

Without any mystery.

MARAT is almost in the clink;

So let’s restore ourselves with a dose

Of this frothy cocoa drink.”

However in the meantime.

The Cordeliers District,

Had armed its warriors.

With very many carts,

And those carriages one hails,

The passages are blocked,

And the guns are loaded.

But lest anyone break through

The passage du Commerce,

Two cannons are placed there

With two or three platoons.

By the door, no carriage arch,

To MARAT’S humble dwelling,

Are placed thirty grenadiers,

With fifty riflemen.

Supported fromthe riverside,

The SAINT SEVERIN District

Has prepared its terrain. [4]

When arriving from behind,

The SAINT MARCEL District,

Came to unfurl its banner

In the Place SAINT MICHEL.

NAUDET the great Captain,

Fearing a flanking move

Protected Luxembourg.

D’ANTON, this other TURENNE, [5]

Followed by some warriors,

Visited all the neighbourhoods;

Putting himself out of breath;

Encouraging the soldiery

To defend MARAT well.

Such glory & such fame

Are not acquired without pain!

Father GOD, Cordelier,

Would show no mercy.

But hidden in his attic

Monsieur FABRE D’EGLANTINE

Seeing the civil war

Quivered from head to toe;

More than if he saw the faces

Of the Bailiffs & recorders

Coming to sing his morning prayers.[6]

WASHINGTON’S monkey,

Surrounded by a battalion

And all these subalterns,

Went off prancing,

And nearly grazed in passing

The lampposts & the ropes,

Where he let a treacherous mob

String up poor FOULON. [7]

He sees that canons have been placed

On every avenue;

And that the end of every street

Armed like a bastion,

Contains a large battalion:

This troubles his genius,

And his soul is less bold

BARNAVE is quite astonished;

He was determined

To act like he’d done at Versailles;

But to risk battle and die!

D'AIGUILLON, gasping for air

From his fishwife attire

Flees at the double,

Escorted by the rabble. [8]

Brave like RODOMONT,[9]

Suddenly without any warning,

Henri SALM & Jacques AUMONT (7)

Go off to explore;

Everywhere are large platoons:

So Henri says to Jacques;

‘My dear friend, let’s decamp;

Let's not start the attack;

Don’t you see those big canons?’

‘Well said, let’s retreat’;

Jacques immediately replies;

‘Soldiers! Half turn to the right.

The obedient troops

In such pressing danger,

Turn round to find LA FAYETTE;

Whose stunned expression,

Dismayed the proud AUMONT,

And his brave companion.

Bold like NICOMEDES (b)

VILLETTE (8), finding himself there, [10]

Suggests a remedy for the ill.

‘This is really no big deal;

Trickery is as useful in war,

As in love, thank God!

We must outflank the enemy,

And attack it from behind.

On more than one occasion

FREDERIC (c) did the same.

But the assembled Troops

Keep watch and fall silent:

When at this moment,

The mistress of MARAT,

A sturdy chambermaid

And formerconventgatekeeper(9) [11]

Whose eye sparkles bright,

Addresses this prayer,

To the most unfortunate Lover,

Who is causing all her grief.

‘Do you want to be murdered?

Or even in a prison cell,

Without your JAVOTTE, starving [12]

On a shabby straw mat,

Do you want to be confined?

Take my headscarf, my petticoat,

And my cotton kerchief;

I will wear your breeches,

And followed by your JAVOTTE,

Whom they will mistake for a boy,

We will go far from the city

And find another home.

Do you wish to see Paris burn

For a few worthless lines?’

MARAT did not wish to know

But the clever maid

Crying and sobbing,

Knew how to soften up her beau.

‘I'm not worth that much blood,’

Says MARAT, in sensitive mood;

‘Let’s leave the city calm;

And swop our clothes at once;

We can do anything with love.”

This noble disguise

Was done in a trice.

Descending from their attic, [13]

They pass through the Soldiers

Without any hesitation,

And make their way outside.

Arm in arm, the couple

Lengthened their stride;[14]

When on a street corner

They find brother GRUE (10),

A subaltern, but strongwilled [15]

Who recognizes them at once…

He did not cry out in wonder,

But whispers in their ear:

‘You’re doing well,

Go now, have no fear,

Once you're in the clear

I’ll do what needs to be done.’

MARAT responds at once,

‘It’s to spare the blood

Of a District I revere,

That I’m wearing a white petticoat,

Farewell, my reverend frère.

The subaltern Cordelier,

Fearing some grapeshot

Might start the fight;

Cried out across the neighbourhood

In a loud, booming voice:

‘MARAT has chosen his story,

He fled a long time ago.’

They did not want to believe it;

D’ANTON, wanting all the glory

Sends a detachment,

To thoroughly search

His whole apartment,

And assure their escape.

He knew everything in a flash. [16]

Once peace was resolved.

Brother GRUE was dispatched

Towards the great General,

Who welcomed his Ambassador

In a most friendly manner,

And gave him a warm hug.

Immediately, from both sides

The retreat was rung;

And the delighted Bourgeois,

All cried out, PEACE IS DONE.

But dark CRUELTY,

Indignant & furious

At such a treaty,

Quickly takes flight;

And in her fearsome rage

Hastens to the Châtelet

To ponder some misdeed.

STUPIDITY, now more tranquil

Lingered within the Hotel de Ville.

Thus ended, without a melée,

But not without a dumb display,

The adventure of Marat. [17]

Notes to the Last Canto:

(1) Baroness DE STAËL is not unworthy of her father & her mother, she has as much intelligence as beauty; everyone knows that.

(2) Comte Louis DE NARBONNE had left Mademoiselle CONTAT for Madame de STAËL, but, like ANTHONY, he kept returning to CLEOPATRA & the Actress prevailed over the Ambassadress.[18]

(3) Comte DE GUIBERT had been dumped by Madame de STAËL; such a loss consoled him for all his disgrace. [19]

(4) The Marquis de CHAMPCENETZ is the Ambassadress’s nemesis because of this famous epigram which has been falsely attributed to him, & which he has the candour to disavow: [20]

ARMANDE holds in her mind everything she’s read,

ARMANDE has acquired a scorn for charms;

She fears the mocker whom she constantly inspires,

She avoids the lover who does not seek her.

Since she lacks the art of concealing her face,

And she is eager to display her intellect;

One must challenge her to cease being wise,

And to understand what she says. [21]

(5) Bribed writers.

(6) Ditto. [22]

(7) The Prince of SALM & the DUC D'AUMONT sign their names democratically, just as they are written in the poem, which is quite ridiculous.[23] The poor devils are taking revenge for the contempt they have always inspired in honest people & have mingled effortlessly with the rabble.

(8) All Paris knows about VILLETTE, a retroactive citizen. VOLTAIRE died inconsolable for having praised him. [24]

(9) Indeed, MARAT's mistress was a novice in a convent from where she was taken by our hero. [25]

(10) Brother GRUE, the heavyweight of the adventure, is a jolly good fellow who does not lack common sense, & to whom the Cordeliers district owes a statue; but the multitude is ungrateful.[26]

(a) Antagonist of Mr. Necker

(b) The King of Bithynia

(c) The late King of Prussia.

[1] ‘Satyre’ usually refers to the part human, part goat creature, known for revelry and bad behaviour. Possibly a pun, referring to both ‘satire’ and Mme de Stael’s ‘ugliness’, whose masculine looks were frequently commented on by contemporaries.

[2] Champcenetz often inserted himself in the third person into his own compositions.

[3] “Monsieur de Saint-Ecritoire” was Necker’s nickname for his beloved daughter, Herold (1958), p.66. Ecritoire was a portable, hinged desk set.

[4] Actually, it was the militant Saint-Antoine district that Danton threatened to summons into action as backup. Saint-Severin provided a contingent of National Guards for Lafayette’s expedition. See Babut, pp.284-85.

[5] Henri de la Tour d’Auvergne, vicomte de Turenne was a Marshal General of France from the 17th century, renowned for retaking Paris from the Prince de Condé during the civil wars of the Fronde.

[6] Fabre d’Eglantine had been a target for earlier lampoons by Rivarol & Champcenetz in their Le Petit Almanach de nos grands hommes pour l’année 1788 (1788) and Petit Dictionnaire des grands hommes de la Révolution (Aug 1790). Fabre d’Eglantine, who lived four doors away from Marat on 12 rue de l’Ancienne-Comedie, was Danton’s right-hand man and vice-president of the Cordeliers district assembly at this time. While Paré was president (Danton having served from October to December), the district was still effectively under Danton’s control, and Danton was re-elected president on 31 March.

[7] Joseph Foullon de Doué, who replaced Jacques Necker as Controller-General of finances, was deeply unpopular with the Parisians. He was lynched “à la lanterne” on 22 July 1789, and his head stuck on a pike with his mouth stuffed with straw, following a widespread rumour that he had said, “let them eat hay!”.

[8] Armand de Vignerot du Plessis, duc d’Aiguillon had been the wealthiest man in France after the king before sacrificing his title to all his feudal properties on 4 August 1789 and losing over 100,000 livres in rents. Despite having planned to launch the initiative during the debate on renunciation of noble privileges, the considerably less wealthy vicomte de Noailles beat him to the punch in a bid for popularity! Nevertheless, d’Aiguillon’s gesture had a massive impact, and his gesture became the signal for similar sacrifices, escalating events much further along than anticipated. As a result, disgusted royalists, especially from the Actes des apôtres and Gautier’s Journal general de la Cour et de la Ville, depicted him dressed as a poissarde (fisherwoman) leading a battalion of tough dames from Les Halles during the October Days march. Barnave was depicted in similar fashion. In fact, transvestism was frequently deployed in royalist lampoons, as we shall see in the later description of Marat’s escape.

[9] Rodomonte was a major character, renowned for his bravery and arrogance, in Ludovico Ariosto’s 16th-century romantic, epic poems, Orlando innamorato & Orlando furioso.

[10] While the marquis de Villette was the commandant of the Cordeliers district battalion, he opposed Danton’s wish to defend Marat, and had suggested arresting him themselves. Because of the Cordeliers’ own arreté from 19 January insisting on district autonomy, he explained to Lafyette’s commander, Gonsault de Plainville, that he must remain neutral but later thanked him for ridding the district of a “mauvais sujet”. The other battalion commander present was Carle from the Henri IV district. See Babut, p.285

[11] See later note for likely explanation of the convent reference. At this time Marat had a young assistant, Victoire Nayait, who liaised with local printers. This might also explain the erroneous reference to chambermaid.

[12] Javotte is a fictional archetype who often appears as a maidservant, or, sometimes, a prostitute.

[13] Marat had been staying nearby with Boucher de Saint Saveur as a precautionary measure since 14 January. His rooms were in the hotel Fautrière, 39 rue de l’Ancienne-Comédie, which also housed the permanent barracks (30 men) for the Cordeliers district militia. See Mémoire de Madame Boucher Saint-Sauveur contre Marat (late 1790).

[14] According to Marat’s own account of his escape in the Ami du Peuple #170 (23 July 1790), which was also published some six months later, he donned a disguise and left in the arms of a young lady (“marchant à pas comptés”). This detail that might suggest that the poem was published after this account.

[15] The word ‘Coupechou’, a variant of ‘Coupe-choux’, literally means ‘Cabbage cutter’. It was often used in conjunction with ‘frère’ to mean a novice monk (usually put in charge of the vegetables), and, by extension, a person of no importance, Dictionnaire de la langue française (1873), in Dictionnaires d’autrefois (online). In the slang of Père Duchene, ‘grue’ means a fool, or someone easily tricked, Michel Biard, Parlez-vous sans-culotte? (2009), pp.179-80.

[16] When the National Guard were finally allowed to enter Marat’s rooms, they confiscated all his papers, both presses and his type, effectively ending the newspaper and bankrupting him. Many of the papers, including valuable information on Marat’s subscribers, remain in the Archives Nationales (Pierrefitte). The most important of these were rescued by friends, most notably his detailed evidence against Necker, which he published from London in a follow-up to his original pamphlet, as Nouvelle dénoncation contre Necker (April?). Danton’s relationship with Marat would later be lampooned in a scurrilous libelle that described them having homosexual relations, Bordel patriotique etc. (1791).

[17] It is worth nothing here that as a result of Marat’s escapades, his resulting notoriety led to a considerable increase in his revolutionary profile with other journalists and politicians now paying much closer attention to his writing, especially when he began publishing fiercely hostile pamphlets from London. It also led to his inclusion in David’s sketch for his unfinished paining, Serment du Jeu de Paume (1790/91), where Marat can be seen top-right in the public gallery, wearing a broad-rimmed hat, writing with his back to the viewer. The other inclusion, not there at the time, was the deputy Bertrand Barère, editor of the Point du Jour.

[18] In fact, she appears to have had her first two children by the comte de Narbonne-Lara, born in 1790 (Auguste) and 1792 (Albert), see Herold, p.95.

[19] Guibert was a handsome salon gallant and habitué of the salons run by Madame Necker, Mme de Stael’s mother.

[20] Quite why Madame de Stael merits four uncomplimentary notes remains unclear. If Rivarol and/or the marquis de Champcenetz are the anonymous authors, it is worth noting that they also prefaced their anonymous Petit Dictionnaire des grands hommes de la Révolution (Aug 1790) with a biting (and salacious) dedication to “her excellency Madame la Baronne de Stael”, which mocked, amongst other things, the weight of her “prodige” [genius]. Champcenetz also had a fondness for using the six/seven syllable lines found in this poem.

[21] These lines first appeared in a pamphlet erroneously attributed to Rivarol, Réponse à la réponse de M. de Champcenetz; Au sujet de l'Ouvrage de Madame la B. de S***. sur Rousseau (1789), p.7. It is most likely by Champcenetz, who also wrote the original Réponse aux Lettres sur le caractère et les ouvrages de J.J. Rousseau. Bagatelle que vingt libraires ont refusé de faire imprimer (1789). He had also used the alter ego ‘Armande’ to describe Mme de Stael in the anonymous Petit traité de l’amour des femmes pour les sots (1788). The reference to the mother-worshiping Armande comes from Molière’s play, Les Femmes Savantes. The satire is piquant since Mme de Stael was presented by her adoring family as a child prodigy under the tutelage of her doting mother, described by William Beckford as a “précieuse-ridicule”. Moreover, and it is hard to see how the author knew this unless a salon regular, or informed by one, Mme de Stael had privately acted in Les Femmes Savantes. See Helen Borowitz, ‘The unconfessed Précieuse etc.’, in 19th Century French Studies (1982), p.39.

[22] These names suggest someone with intimate knowledge of Necker’s propaganda ‘factory’. Marat had also accused Mercier, Suard and Gudin of being on Necker’s payroll (check). Paul-Philippe Gudin de la Brenellerie, Beaumarchais’s friend and publisher, would later publish a Supplément au Contrat Social (1792, Maradan), which came with an appendix on the need to breed to keep breeding to secure a steady increase in the population! Garat’s Journal de Paris was openly subsidized by Necker. Amongst the more patriotic writers, Cerutti, later editor of La Feuille Villageoise, was also the only one writer to openly defend him in his Lettre sur Necker (1790).

[23] Probably a reference to Charles Albert Henry (b.1761), ninth son of Philip Joseph, Prince of Salm-Kyrburg.

[24] Charles (the former marquis) de Villette was a noted homosexual frequently attacked in scurrilous pamphlets during this time, including, Vie privée et public du ci-derrière marquis de Villette, citoyen rétroactif (1791) and Les Enfants de Sodome à l’Assemblée Nationale etc. (1790, ‘Chez le Marquis de Villette’). ‘Rétroactif’ here appears to be both a pun on being an ‘active’ citizen (referring to the law passed in Oct 1789, discriminating between active and passive citizens for the purpose of voting and standing for office, and a possible synonym for homosexuality (viz its synonym, ‘posterior’).

[25] This reference to an imaginary, ex-novice lover probably alludes to a recent article in Marat’s paper, describing how his services were regularly sought by readers seeking redress. In this particular issue (Ami du peuple #88, from 5 Jan 1790), he gave the singular example (“aussi piquante par sa singularité qu’elle est intéressante par sa nature”) of a nun called “sister Catherine” (Anne Barbier) who had escaped from Pantémon Abbey after suffering countless abuses due to her patriotic views. She had come to see Marat in the company of her landlady (Mme Lavoire), she had sought his help in securing her liberty and reclaiming her possessions.

[26] While I can find no trace of a ‘brother Grue’ in any of the surviving accounts, the most likely candidate would appear to be the powerfully built butcher, Louis Legendre, co-founder of the Cordeliers Club in April 1790 with Danton. In this context, ‘Lourdis’ probably derives from the figurative use of ‘lourd’ to suggest heavyweight, possibly by association with the other meaning of ‘grue’ as ‘crane’ (both bird and a lifting mechanism for heavy loads). Legendre hid Marat several times in his cellar on the rue de Beaune; see speech to the Jacobins on 24 Jan 1794, in Aulard, op.cit.

Alternatively, a letter from 9 May 1790 describes the arrest of Louis Gruet, a fusilier in the Cordeliers battalion. See Alexandre Tuetey, Répertoire général des sources manuscrites de l’histoire de Paris pendant la Révolution française, Tome 2 (1890), p.420 (3982).

Finally, ‘Grue’ might be a nickname for François Heron (viz ‘crane’), who later acquired notoriety as the main police agent for the Committee of General Security. While I can find no record of his playing any role in these events, he also hid Marat in his home, on 275 rue St Honoré, during 1790, and probably knew him from their time working for the king’s youngest brother, the comte d’Artois.

#la fuite de Marat#Jean-Paul Marat#French Revolution#Georges Danton#General Lafayette#libel#counter-revolutionary#poetry#1790#Jacques Necker#marat

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anon [Louis de Champcenetz?], The War of the Districts, or the Flight of Marat, Heroi-comical poem in three cantos (Paris: n.p., July? 1790)

Part 3 (of 5)

Second Canto:

When the croak of the frogs

And the screeching of owls

Had warned the patrols to

Monitor passers-by;

And numerous clocks have

Already struck midnight,

An Allobroges Goddess [1]

Emerged from her dark lair.

Her seat is City hall;

It's there, in an armchair

That she gazes lovingly

At this civilian cohort

From whose pride all Paris suffers.

FAUCHET, this sinister abbé, (1) [2]

Is the lover & minister

Of this Divinity,

Whose eye is completely dulled.

This is where FAUCHET reflects:

And it is she who inspires him,

When he makes those eloquent speeches,

Which, dismaying our monarchy

In Paris, and the Provinces,

Progress so rapidly.

This famous Goddess

Is quite rotund with fat:

She walks heavily,

Laughs & cries at any time,

Without any direct cause.

She used to live in Greece

At a time when its bourgeois

Were performing heroic feats everywhere.

But it was in BOEOTIA* [3]

That she had spent her life:

Since then, having in many places,

Made herself a homeland,

It was Paris she chose.

On a chariot made of donkey skin.

Supported by twenty goslings,

In the air that we breathe,

She glides, she soars.

She walks without pretense,

And her sceptre is a poppy.

At her feet are the works,

And audacious prattle

Of factious writers

Whose foolish pride renders so vain.

The Goddess protects them all,

And her chariot is crammed

With the works of CÉRUTTI. (2)

She enjoys the MANEGE; [4]

The comte de MIRABEAU

Is a true beacon for her.

A thousand college know-it-alls,

Modern-day jackasses, [5]

Like the TARGETS, the PÉTIONS, (3)

The DUPORTS & the DUPONS, [6]

And all their varied retinue,

Like so many antique CICEROS;

For whom the eloquent Goddess,

With all her skill,

Dictated the motions.

But I have to say

Who is this Deity

That has held me back for so long?

She is the sister of STUPIDITY,

And her name is IMBECILITY.

This Queen of bystanders,

Having learned the work

Of the district of OBSERVANCE;* [7]

Enters without a torch,

And slips silently into

The house of the famous MIRABEAU. (4)

She noticed this large man

Who lay in deep slumber.

In his hands a portrait lay,

Where a bookseller's wife, (5)

A loathsome housekeeper,

Was faithfully portrayed.[8]

Under his heavy head,

Nestling beneath the pillow,

COWARDICE could be seen,

His dear Divinity.

Terrified by the slightest sound:

One only has to stare at her

To make her ill at ease.

She is cunning & cautious;

She fears getting involved

In the slightest danger.

Her gait is unsteady.

Her sad & shy voice

Is quite insinuating.

Frog & hare both at once,

Its features are repulsive.

Like a bat,

She has two wings under her arms;

It’s to flee from her enemies

And those who stir up trouble.

She got to know MIRABEAU

When he was in his cradle.

She’s his faithful companion,

He is her strongest support;

And since he is worthy of her,

She is very worthy of him.

But on his broad chest,

In the guise of a nightmare

A haggard monster slept supine,

Whose dreadful & sullen face,

Sends shivers down the spine.

It constantly sharpens a dart,

And in its barbaric joy

Seeks his prey everywhere.

Its claw is sharp & hard;

Its eyes are bloodshot;

An ever burning hunger

Consumes & torments it.

This dreaded monster,

Its name is CRUELTY.

Its usual refuge,

Is the Châtelet’s black lair,

And with a menacing blade,

It strikes the innocent there.* [9]

While speaking in his ear,

STUPIDITY wakes her up.

‘Cousin! How can you sleep?

Soon the hour will come,

Where my darling LA FAYETTE,

Awakened by the trumpet,

Must ride on his horse,

To make a capital blow.

They wish to take the great MARAT,

To lock him away behind bars;

His District wants to defend him

And prepare its cannon [artillery].

The warriors of OBSERVANCE

Have made more than one alliance;

The SAINT-SEVERIN District

Must lend it a hand.

They have other assistance too,

And the Faubourg SAINT-MARCEAU

Is going to use its Flag.

In this terrible affair

Cousin! what should we do?’

Smiling CRUELTY

Said to her: ‘We will have blood’.

Its eye sparkles with joy,

And his fearsome pupil

Lighting up like a torch,

Covers MIRABEAU in light.

Without waking him up,

It warns him in a dream,

About the fight in question;

Here is what the response was,

From this truly great man.

‘The Districts are my friends

And it is through them that I reign;

Above all, I must fear

To make them my enemies.

Such stupid revenge

For this poor La Fayette

Has wonderful charms;

I will not follow in his footsteps.

But I do like fights,

When I’m not running away from them’.

COWARDICE applauds

Such a prudent speech,

Gets up from where she’s sitting;

Admires this great genius,

And says to CRUELTY

Who is not his enemy:

‘Proceed another way.

BARNAVE is full of zeal,

The LAMETHS are not lacking;

D'AIGUILLON (6) the prattler,

And so many other good Soldiers,

Will join you in the battle’.

To these words without rejoinder,

CRUELTY slips out mute,

And STUPIDITY follows suit.

BARNAVE, with his gaunt face,

Was the first to be visited.

By the loathsome couple.

BARNAVE, bloodthirsty heart.

First became the pupil

Of the Philosophe MOUNIER: